Angharad Williams and Sophie Gogl

November 1st - December 18th, 2022

Sometimes inequality is better expressed through abstract numbers than the pathos of individual

trauma narratives. Numbers allow us to see that the problem of economic inequality is not one between fine habitual distinctions, but between millions and billions that remain forever unimaginable. That’s why the great communist thinker Bini Adamczak makes complicated calculations and recently tweeted that a cashier working full time at the German discounter Lidl at a maximum gross annual salary of €33,0000 would need 1.4 million years or 37,176 working lives to become as filthy rich as the Lidl owner, who has only one life, is now.’

Like most of us, the Lidl cashier needs a work-life balance. 37,176 work lives make 37,176 private lives makes 74,352 mothers and fathers, which makes 37,176 Oedipal triangular constellations, a strange mosaic, a beautiful massacre. If Kafka were a Lidl cashier with 37,176 lives, the letter to his father would have about 371,760,00 pages. Many lives, many lines. All these injuries, all these reproaches. Since there was nothing at all I was certain of, since I needed to be provided at every instant with a new confirmation of my existence, since nothing was in my very own, undoubted, sole possession, determined unequivocally only by me — in sober truth a disinherited son — naturally I became unsure even of the thing nearest to me, my own body. Many reproaches would come back from the many fathers, one, in life no. 23,459 would say, “You frowning rat on your high horse, which was meant as an insult against the cashier’s new wealth, which, according to her family, had changed her ‘habitus.’ She would reply, hurt and exhausted, “That's rude to animals” and “I worked hard for that!”.

Germans have an average of 3.4 serious love relationships in their lives. The Lidl cashier, if she were an average German, would have 126,398,4 relationships during her 37,176 lives. If she had a broken heart after half of these relationships, she would have 63,199,2 broken hearts. That adds up to many hours of love sickness, a few kilos more and many unfashionable short haircuts, at least a third of which, that is 21,066,4 haircuts, make her look not younger but more miserable, like she works a lot. But if you are a worker that loves so much, too much, maybe it won’t hurt at all, after a while. Love is love is love is love is love is love is love is love. After some lives, the signifier (love) refers to nothing but the signifier love. The signified has long since fucked off, right after the half-time of the cashier’s 37,176 lives, that is after 18,588 lives. Work, however, unlike love, remains (material) and means something (exhaustion, expropriation). I know that maybe, my calculation won’t add up.

My sister, who works in a project called TakeHeart, which partly funded Bini Adamczak’s calculations, has a gross annual income of €43,200, slightly more than the Lidl cashier. My sister would need 1.1 million years, or 28,350 working lives, to become as filthy rich as the Lidl owner is now. But my sister, like me, has a strenuous relationship with money. We love to waste it all away. That comes from the parents. It’s hard to get rid of, like intergenerational trauma. Because of her inherited wastefulness, even after 37,176 lives of work, my sister probably wouldn’t own as much money as the owner of Lidl owns in just one lifetime.

Recently, I had a dream in which my sister, at the end of her 28,350 working lives, was analyzing her relationship with money using a therapeutic method called systemic family constellations. In attempting to uncover the unrecognized money dynamics that span her many family lives and to resolve the damaging effects of that dynamic through representatives in order to face and accept the

factual reality of the past, she encountered systemic entanglements. When I woke up, I said to myself: “Our whole lives, we’ve been workers. From now on, we’re pleasure seekers!”

-Sophia Roxane Rohwetter

Angharad Williams (b. Ynys Môn, Wales), selected solo exhibitions include Eraser, Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf; Picture the Others, MOSTYN, Llandudno (both 2022); High Horse, Kevin Space, Vienna (2021); Without the scales, Schiefe Zähne, Berlin (2020); Witness, Haus Zur Liebe, Schaffhausen; Island Mentality, Peak, London (both 2019), Scarecrows, Liszt, Berlin (2018). Performances, and group projects have taken place at Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn (2022); FriArt, Fribourg (2021); KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; Stadtgalerie Bern, Bern; Kunstverein Munich, Munich (all 2020); ICA, London; No Bounds Festival, Sheffield (both 2019).

Sophie Gogl (b. Kitzbühl. 1992), selected solo exhibitions include Klein Beestjes, La Maison De Rendezvous, Brussels (2022); Jars, KOW, Berlin 2022. (2021), Storno, curated by Marlies Wirth, MAK - Museum for Applied Arts, Vienna (2020); Secondhand Angst, Zeller van Alsmsick (2018); Vienna; Young and Concerned, Zeller Van Almsick, Vienna (2019). Selected group shows include: La Réforme de Pooky, Kunsthalle Friart, Freiburg (2021); No Dandy, No Fun, curated by Valérie Knoll, Kunsthalle Bern (2020).

Angharad Williams

Untitled (1-18) #18 FI

2022

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 72 inches

Untitled (1-18) #18 FI

2022

Acrylic on canvas

48 x 72 inches

Angharad Williams

Untitled (1-18) #10 KS

2021

Acrylic on canvas

39.125 x 27.25 inches

Untitled (1-18) #10 KS

2021

Acrylic on canvas

39.125 x 27.25 inches

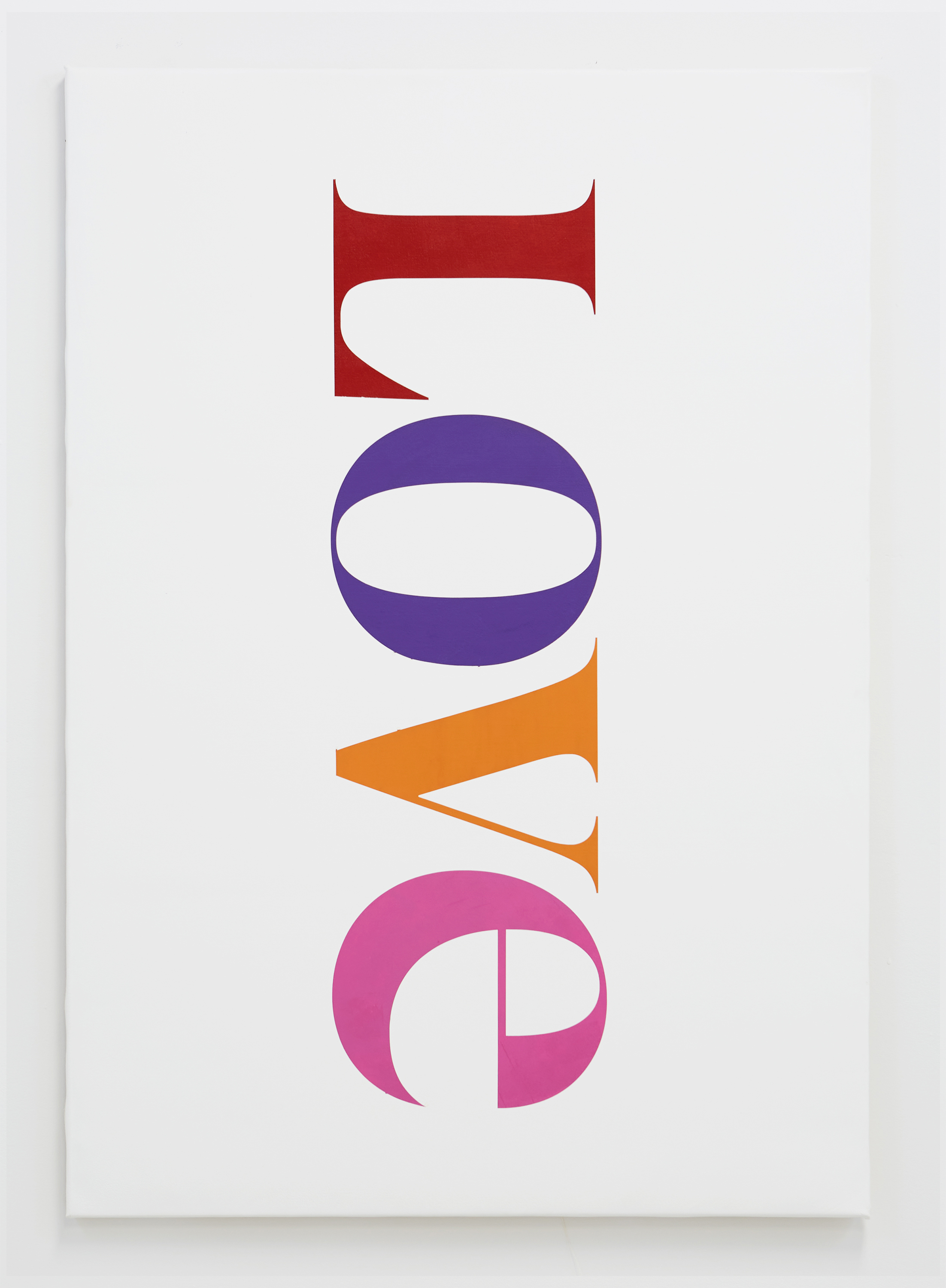

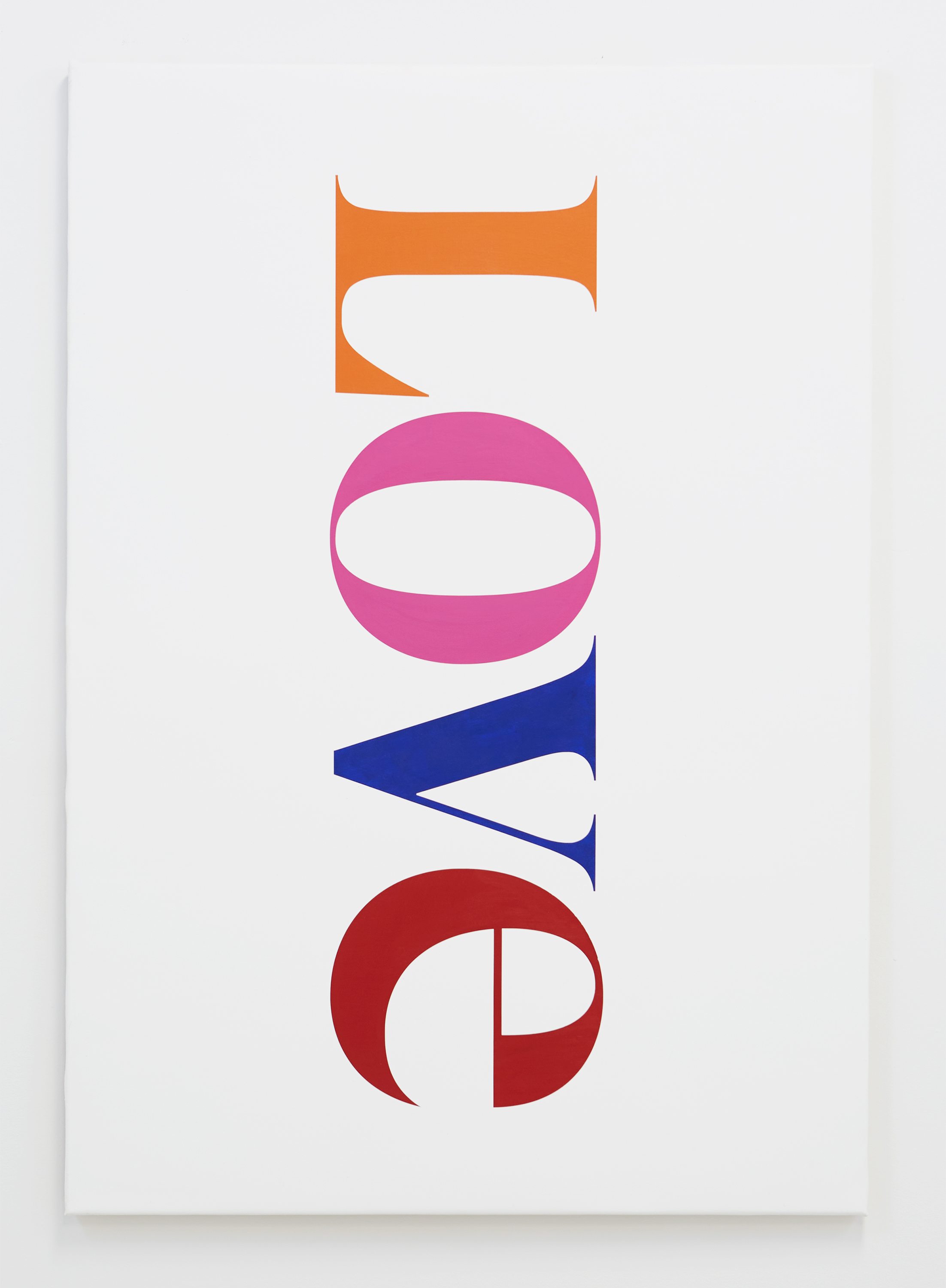

Angharad Williams

Untitled (1-18) #17 KS

2021

Acrylic on canvas

39.125 x 27.25 inches

Untitled (1-18) #17 KS

2021

Acrylic on canvas

39.125 x 27.25 inches

Sophie Gogl

Cute

2021

16 x 12 inches

Acrylic on panel

Cute

2021

16 x 12 inches

Acrylic on panel

Angharad Williams

Nobody Wins

2021

Glass

12 x 1.5 x 1.25 inches

Nobody Wins

2021

Glass

12 x 1.5 x 1.25 inches

Sophie Gogl

plastikvogel

2021

Acrylic on panel

94.5 x 67 inches

Courtesy Private collection, New York

plastikvogel

2021

Acrylic on panel

94.5 x 67 inches

Courtesy Private collection, New York

Documentation by Iain Emaline and Daniel Terna